Getting under the skin of Whittaker’s, Lindt, and confectionary

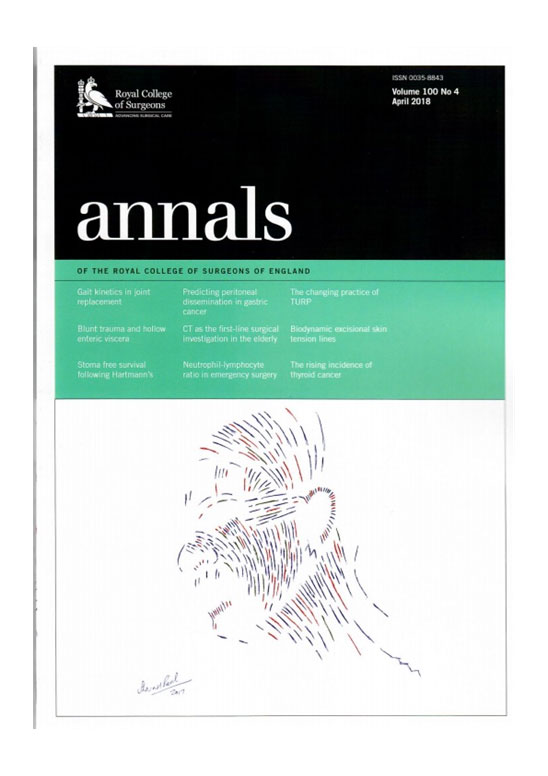

A few years ago, I developed the concept of “biodynamic excisional skin tension lines” (BEST lines) essentially to understand skin tension, and to figure out the best way to excise skin cancer and obtain the best results. These BEST lines are now considered the “first major new concept in skin tension lines since Langer’s cleavage lines in 1861” in the review of my book published by Springer Nature. My work (and signature) even made the cover of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. It is probably considered the biggest achievement in my research career.

However, the first thing I realised while studying the biomechanics of skin to advance the science is that skin behaves like an elastic solid. Technically from an engineering perspective it is an elastic solid on a continuum foundation. Secondly, our perception of substances that come in contact with our skin depend on how these two—essentially moving—membranes react. The science and engineering of such interacting surfaces in relative motion is what is called tribology. And this convergence of sciences interests me because I run a skincare and cosmetics research lab, and I love chocolate. How are these two linked?

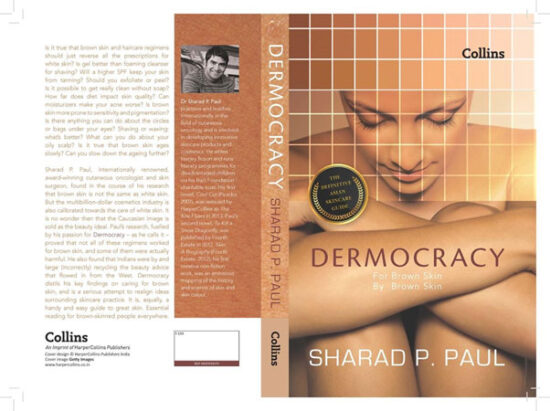

Let’s go back to some basics of making skincare creams. I wrote about making skincare and what you can do at home in a book, Dermocracy: The Definitive Asian Skincare Guide (Collins, 2015), a few years ago.

In essence, you make moisturisers either by using oil-in-water or water-in-oil formulations. Oil-in-water contains mainly water in which the oil is virtually dissolved due to the abundance of water content. These make up the bulk of formulations because they are less greasy. However, the water evaporates in hot conditions, making them less effective. Water-in-oil is mostly oil in which water has been dissolved by dilution. Such formulations make skin shinier and feel warmer. Wondering why some moisturisers make you sweat? It is because water-in-oil formulations are not good in warm conditions i.e., if you were using them as day creams.

Once you’ve made a water-in-oil or an oil-in-water formulation, the next step is customizing them for different body areas. As a general guide to the composition of moisturisers, body lotions are made up of 10 to 15 per cent in the oil phase and 75 to 85 per cent in the water phase, which is why they are lotions and runnier. The remaining 5 per cent are humectants (more on this below) like glycerine.

Hand creams, for example, contain 20–40 per cent in the oil phase and 40–60 per cent in the water phase and 15 percent humectants, making them a lot thicker. Hand creams are the thickest of all formulations because they need to penetrate the extra cuticle layer found on palms and soles.

When it comes to moisturising skin or using emollients to make skin supple you have two techniques—barrier (occlusive) methods where you use something to create a barrier on your skin which traps the water inside the skin and prevents it from evaporating. Examples would be Vaseline, petroleum jelly and body butters. The other way to retain moisture in your skin is to use a humectant—something that draws in moisture. For example, glycerine or glycerol is a humectant which has three OH groups desperately waiting to stick to water, and only three carbons. In my skincare range, I have a range of serums containing synthetic forms of hyaluronic acid—naturally occurring in skin, eyes, and joints—that is capable of binding over one thousand times its weight in water.

What’s all this got to do with the price of chocolate fish? The secret is to do with tactile sensations—how our bodily membranes feel things—which is related to the science of tribology. When it comes to skin, we know that when we apply a skin cream, the following occur—the spectral centroid, adhesive force, and coefficient of friction increase whereas the vertical deviation decreases, which corresponds to how we perceive something to be fine, greasy, sticky, and smooth on our skin. And the friction coefficient, usually denoted as μ, is around 0.2-0.5 when our skin is dry, but in the case of moist or wet skin one measures higher friction coefficients, typically much higher e.g., >1.

In the case of chocolate, tribology suggests the importance of where fat is located in a formulation i.e., a cocoa-in-fat or fat-in-cocoa scenario. Anwesha Sarkar, Professor of Colloids and Surfaces in the School of Food Science and Nutrition at Leeds University, has been quoted[2] as saying: “Lubrication science gives mechanistic insights into how food actually feels in the mouth. You can use that knowledge to design food with better taste, texture, or health benefits.” For those interested in the technical aspects of this study, you can find a link here.

Typically adding fat makes foods “more-ish” as food companies have long known. This is due to the part of the brain—our “hedonic cortex” that includes areas such as the orbitofrontal regions—that is responsible for memory and sensory pleasure. This is because primitive man had to hunt or gather foods. Food was not plentiful and chasing animals for their calories was both crucial and critical, and the lack of sustenance could have been calamitous for our species. Life over death. Our collective genes evolved for survival, and our brains became evolutionarily wired to want fatty tastes because fats are the highest source of energy. The amount of energy delivered by the different food groups is as follows: carbohydrates – 16.7kJ per gram (4 calories); protein – 16.7kJ per gram (4 calories); fat – 37.7kJ per gram (9 calories).

Typically adding fat makes foods “more-ish” as food companies have long known. This is due to the part of the brain—our “hedonic cortex” that includes areas such as the orbitofrontal regions—that is responsible for memory and sensory pleasure. This is because primitive man had to hunt or gather foods. Food was not plentiful and chasing animals for their calories was both crucial and critical, and the lack of sustenance could have been calamitous for our species. Life over death. Our collective genes evolved for survival, and our brains became evolutionarily wired to want fatty tastes because fats are the highest source of energy. The amount of energy delivered by the different food groups is as follows: carbohydrates – 16.7kJ per gram (4 calories); protein – 16.7kJ per gram (4 calories); fat – 37.7kJ per gram (9 calories).

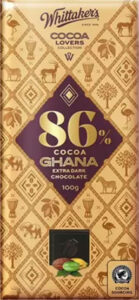

Tribology plays a key function almost immediately when a piece of chocolate is in contact with the tongue. If one has a layer of fat on the outside on a piece of chocolate, it changes from a solid into a smooth emulsion that we find totally irresistible. Undertaking this analysis, I now know why I love Whittaker’s dark chocolates. Whitaker’s—an iconic New Zealand chocolate brand that has existed for more than a century—are not as fatty as many other chocolates but have a fat lining on the outside and that is what makes them delicious. I’ve tried several others with the same cocoa percentage—Lindt is pretty good in this regard as well with a similar coating, but I didn’t find others I tested have mastered the tribology. By the way, my favourite is Whittaker’s 86% chocolate. Like a Goldilocks bear, after trying different percentages I have settled on this as my preference.

THE END

Written By

Dr Sharad Paul

Dr Sharad Paul is an award winning, world renowned recognised skin-cancer expert and thought-leader.