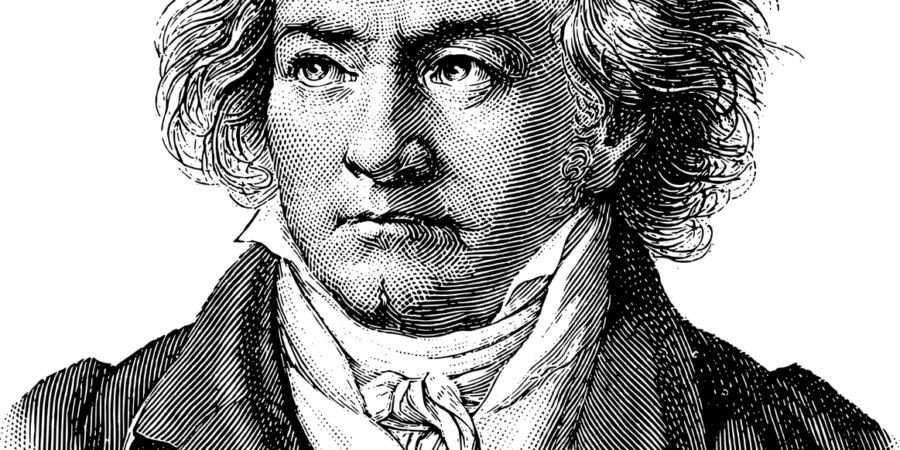

New genetic research lays bare the genius of Beethoven.

Ludwig Van Beethoven breathed his last in 1827, almost 200 years ago. He was 56. The Ninth Symphony was Beethoven’s last work. It was completed and performed, together with movements from the Missa Solemnis and the overture from Opus 124, with great appreciation at the Kärntnertor Theatre. It is said that the concertgoers applauded with an impassioned intensity that was overwhelming to everyone present. However, Beethoven could not hear the audience’s applause. He was almost fully deaf by the time he had composed this piece.

Beethoven monumental achievements meant that instrumental music was elevated to a highly regarded art, a position previously only held by painting and literature. In a letter from Bettina von Arnim to Goethe on 28 May 1810, Beethoven was reported as saying: “Music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy.” What kind of a man could compose these magical pieces he could not hear with his own ears? If this was puzzling to others, Beethoven himself was curious about his own health. Throughout his life, he was troubled with abdominal pains, mood changes and depression, and was gradually losing his hearing. In 1802, already aware of his mortality at the age of 32, he wrote to his brothers asking that they ensure that his doctor and friend, Johann Adam Schmidt, detail his medical history to the public after his death. Unfortunately, Dr Schmidt died well before Beethoven did and was replaced by another physician, Johann Baptist Malfatti. It is said that Beethoven fell in love with the doctor’s daughter, Therese Malfatti, and had indeed written Bagatelle No.25 in A minor for her as “Für Therese” which was mistakenly transcribed by Ludwig Nohl as “Für Elise”. Beethoven had in fact proposed to Therese Malfatti at one point, and she even had the original manuscript of this piece in her possession. Another theory is that this piece was dedicated to a famous German soprano named Elisabeth Röckel.

No composer since Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart had so entirely dominated an art form as Beethoven had. It was a truth of which he was unrepentantly aware of, writing in a note left behind for Prince Lichnowsky at his estate in Grätz, 1806: “There are many princes and noblemen. There is only one Beethoven”.

Recently, Tristan Begg, a Beethoven fan and social anthropologist and geneticist assembled a team to study Beethoven’s genome from the remains of his hair. Begg, now at Cambridge University, was aware that there had been some locks of Beethoven’s hair that had been preserved. Could Beethoven’s curls provide answers to those curious about his life?

The lineaments of Beethoven’s tresses are part of musical legend. It was said that Ferdinand Hiller, a contemporary composer had snipped off a lock of Beethoven’s hair at his funeral! However, genetic studies on these so-called “Hiller’s locks” showed that the hair was actually from an Ashkenazi Jewish woman. Johann Andreas Stumpff, a friend of Beethoven had some hair samples and an autographed letter, and these proved to be the real article.

The research team was able to analyse about two-thirds of the genome, which they analysed for known disease-causing genetic sequences, in homage to Beethoven’s own questions about his medical mysteries. After all, for most of his life, he seemed to have been beaten down by his demons and had taken solace in drink. But his fondness for alcohol, rather than reshaping his musical dramaturgy may have squeezed some of the vitality out of his life.

We now know the cause of Beethoven’s abdominal symptoms. Beethoven had two copies of a particular variant of the PNPLA3 gene, which is linked to liver cirrhosis. He also had single copies of two variants of a HFE gene that causes haemochromatosis, a condition that damages the liver. Both these conditions are severely aggravated by alcohol and can explain the jaundice and swollen limbs he developed later in life. Genetic tests for lactose and gluten intolerance proved negative. However, Beethoven was found to have been infected with the hepatitis B virus that also causes liver damage.

Answers to Beethoven’s hearing loss proved more elusive. Previously, medical folk suspected Paget’s Disease, because a post-mortem examination after the composer’s death had revealed a skull twice as thick as normal. In Paget’s Disease, new bone tissue gradually replaces old bone tissue, making bones fragile and misshapen. When it affects the skull, it can cause deafness. Others suspected Otosclerosis wherein one of the bones in the middle ear, the stapes, becomes stuck in place leading to deafness. Gene tests did not reveal any answers here, and there are no markers specific for otosclerosis anyway. However, I have a theory here. As someone interested in the genetics of health, I was surprised that iron overload that would have resulted from Beethoven’s haemachromatosis has not been further looked into as a potential cause. Other studies that have investigated genetic variants for the ferroportin gene (FPN1; SLC40A1), amino acidic substitutions p.H63D and p.C282Y in the hereditary hemochromatosis protein (HFE), and a polymorphism in the HEPC gene, which encodes the protein hepcidin (HAMP), suggest that a variant of the SLC40A1 gene has an OR (odds ratio) of 4.27 for idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss i.e., people with this variant are four times more likely to develop hearing loss. This was not tested for. I suspect that iron homeostasis in the inner ear could be linked to Beethoven’s hearing loss, and iron overload easily explains his skin pigmentation and depression.

As a skin doctor, I know that increased skin pigmentation affects the majority of patients with iron overload diseases. Skin pigmentation in sun-exposed areas is often one of the first signs of haemchromatosis and may precede other features by many years. Further, studies have shown that people with genetic haemochromatosis experience some level of anxiety and 79% suffer from depression. A study from Dunedin in New Zealand showed that higher iron levels can lead to low mood in young men but not women. Beethoven had himself written about his negative thoughts and suicidal ideation. Beethoven’s darker complexion has previously been well documented. If fact, because of Beethoven’s skin hyperpigmentation, during the Civil Rights movement, people like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael have been quoted as railing against white supremacy saying, “Beethoven was as black as you and I.” Genetic studies done recently, however, do not reveal any African or Moorish descent. But they revealed something more interesting. The Y chromosome in the hair samples didn’t match anyone who shares a 14th century ancestor with Beethoven and there are a few van Beethoven’s alive in Belgium today. Tristan Begg’s ancestry studies reveal a probable affair sometime between the 1572 conception of Hendrik van Beethoven, an ancestor in Beethoven’s paternal lineage seven generations removed from the composer, and the birth of baby Beethoven in Bonn in December 1770. Ludwig Van Beethoven was not a Beethoven after all.

Whoever his real ancestor was, Beethoven ended up perhaps the most confessional of all the great European composers. For all that Beethoven spoke of his miseries and maladies, when we listen to his music what we hear is a joyful soliloquy, unimaginably pleasing yet easy to listen to, with a loving connection to his audience that spans centuries.

THE END

Written By

Dr Sharad Paul

Dr Sharad Paul is an award winning, world renowned recognised skin-cancer expert and thought-leader.