Crime seems to be everywhere in New Zealand – shootings, stabbings, ram raids that even made an embattled government declare the latter—essentially retail crime—a “special crime.” With elections imminent, we see the malice play out in parliament, and discussed in workplaces. A society that values blunt aggression in sport finds itself shattered by criminal activity that is at its most anarchic.

Firstly, if anyone is wondering about the topic of this blog because I usually write about skin, health and wellness, I offer this link: Increased neighborhood crime leads to poorer health outcomes. A few years ago, a master’s degree thesis at the University of Canterbury looked at the association between crime and health at a neighborhood level and found a statistically significant association. There are numerous other international studies on the same theme drawing the same conclusion. Community crime increases stress levels and is overall bad for the health of a population.

What made me reflect on this topic was the recent case of a defenseless man violently attacked inside a McDonald’s restaurant in Hāwera (Taranaki, New Zealand) by the Black Power gang. His crime: wearing a red shirt. It is well known that Taranaki in New Zealand is considered a stronghold of the Black Power gang.

This red shirt and gang-violence story took me to a time around 30 years ago, when I had worked as a locum doctor in Kaitaia, Northland, in the surgical department. In those days, the hospital had a full-fledged emergency department. On my first night, I had to deal with a family that had sustained burns for wearing a red T-shirt (I remember it was a Lion Red—a NZ lager beer brand’s—T-shirt). The family was in a campervan when a gangster in town had noted red shirts and decided to firebomb the van, never mind that there were some young kids in the van who sustained burn injuries. I had only been in New Zealand for two years at that time and it was an introduction into New Zealand’s gangland warfare that innocent people get caught up in unwittingly. That was before Google existed. For those readers that live outside New Zealand, criminal gangs have a surprisingly visible and pervasive presence in New Zealand society, and even a Wikipedia page lists New Zealand gangs including the Mongrel Mob and Black Power. However, before I migrated to New Zealand, my residency training was in plastic surgery—especially burns and trauma—so I could put my skills to use in that small town hospital on that day and attend to those innocent victims.

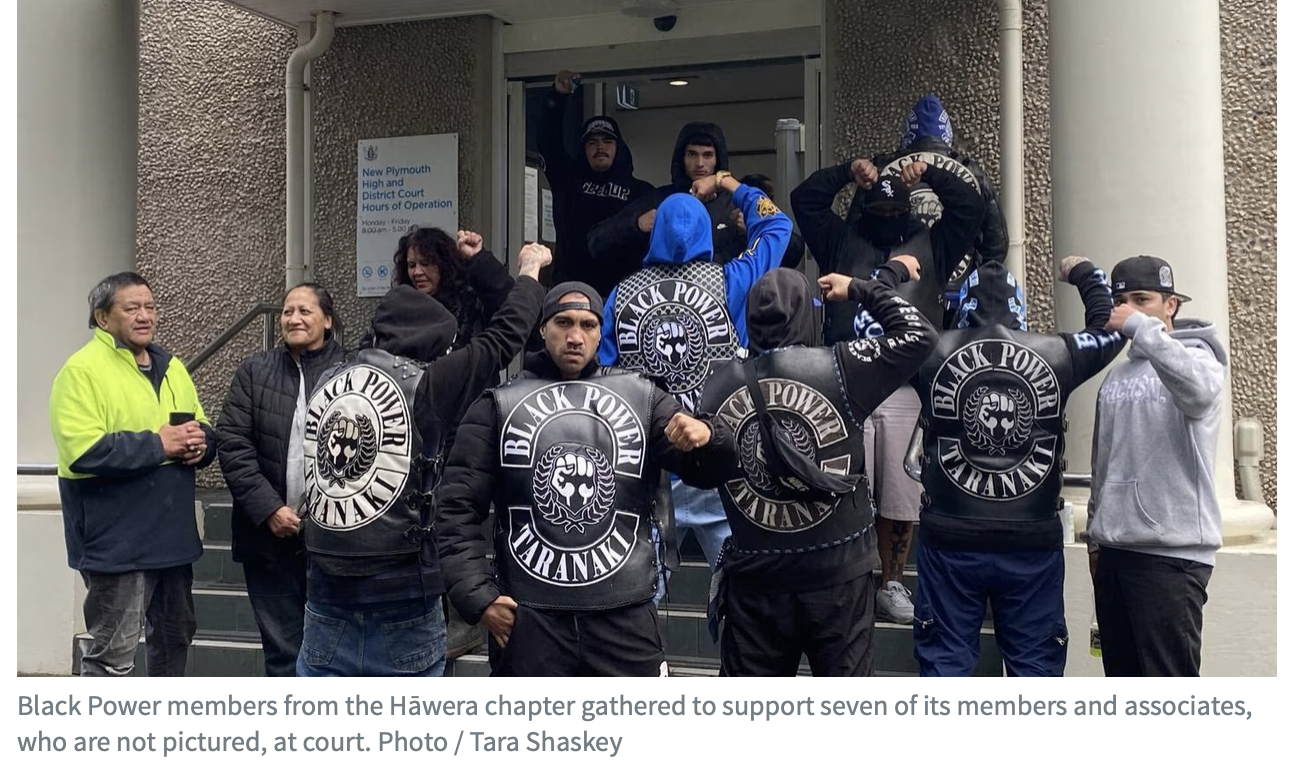

The person who was brutally beaten in this recent Taranaki case I mentioned above was a person with a mental illness and his crime was wearing a red shirt, a color that has been adopted by the Mongrel Mob, one of the Black Power’s main rivals. Reading this story made me outraged on many levels. Firstly, the man had a health disability, pleaded with attackers that he was not associated with any gang (which would have been obvious), and walking up to the restaurant was his only regular social activity (the staff even knew his usual order). According to the report in the NZ Herald, 13 Black Power members and associates took part in this attack on one person—who was stabbed and brutally beaten—at the Hāwera McDonald’s in South Taranaki on September 12 last year, as staff and diners watched on in horror. New Zealand’s newspapers reported that during the sentencing of the gang members involved in the attack, the public gallery was packed to capacity with gang supporters, who raised clenched fists and yelled the gang’s slogan “yoza” in tribute to their comrades in court (image below from the NZ Herald 1 July 2023). Reading this made me wonder: What sort of person celebrates a person, or mates who have ruthlessly beaten a defenseless man? Is that the society we have become, or want, in New Zealand? Where is the sense or moral right and wrong?

If this case wasn’t enough—the scenes are now repeated daily in our newspapers—there was a report of a teenaged Mongrel Mob member who broke into the home of a pregnant woman and indecently assaulted her in the bed she was sharing with her child. His sentence: home detention. The journalist reported that as he walked from the dock after receiving the sentence he yelled “cracked it” in celebration. Is this the kind of victory we want our young men to gloat about?

After World War I, theories on how to develop cities and good neighbourhoods were commonplace and this is where the “six degrees of separation” theory emerged. Hungarian author Frigyes Karinthy published a volume of short stories titled Everything Is Different. In one of the stories, Karinthy wrote: “He bet us that, using no more than five individuals, one of whom is a personal acquaintance, he could contact the selected individual using nothing except the network of personal acquaintances.” It is said in a small population like New Zealand, there are only two degrees of separation (hence the name of the cellphone company). What this means is someone is more likely to become a victim of crime in New Zealand and explains how everyone happens to know someone who is a victim. During my recent trip to America, all the houses I stayed in (in Houston, New Jersey and Los Angeles) had no front or back fences, and backyards just merged onto grassy knolls–something we would find scary in New Zealand cities.

A few years ago, I was visiting a friend in Singapore during a stopover. He had moved to Singapore to join his daughters who studied at the National University of Singapore. He mentioned that the family had chosen Singapore over countries like New Zealand because they could be assured of the girls’ safety during student activities and nightlife. Hearing this reminded me of a report I had read around that time by Zachary Reynolds, an American Law student on an exchange program from the University of Chicago. In 2017, when Reynolds interviewed a fellow alumnus from Chicago living in Singapore, he wrote that the man he spoke to was never concerned for the safety of his teenage daughter regardless of from where, when, or how she came home at night. Singapore has one of the lowest rates worldwide: 0.2 per 100,000 in 2013. Violent crime in general is virtually unheard of. In 2015, the total number of reported violent crimes was less than 4,500 in a city with a population of over 5.5 million. Reynolds wrote: “Walking along the streets of Singapore, several observations, or the lack thereof, strike even the most casual tourist. There is no litter cluttering the streets. There are no beggars asking for change. There is no graffiti marring public buildings. Vandalism is nonexistent. Signs prohibiting loitering are unnecessary because there do not seem to be any loiterers…To an American, the differences are stark. Of course, a system exercising such strict social control involves many trade-offs, but on the whole the effect is undeniably pleasant… First, there is a strong sentiment of public morality that acts as a powerful deterrent to criminal activity. This sense of morality arises from a pervasive Confucianist ethic that emphasizes the importance of “right behavior” as well as the powerful vision for Singapore that its founder, Lee Kuan Yew, instilled in the society, and it manifests itself through the formation of citizen watch groups, creation of blogs and websites devoted to reporting unacceptable behavior of other citizens, and a strong aversion to shaming sentences. Second, prosecutors enjoy an immense amount of freedom with respect to how they chose to handle low level offences”. So interestingly, Singapore does not use shame to punish the offender, but demands moral responsibility from all its citizens.

In the year before Reynolds wrote his report, Singapore had reported 135 days that were completely free from any snatch theft, housebreaking, and robbery. A third of the year without a single such offence recorded! In contrast, the Department of Justice of the New Zealand government recorded 25,494 violent offences (“acts intended to cause injury”) and another 5465 sexual assaults in a population about 10% lower than Singapore.

We may laugh that Singapore is not a democracy, and hypocritically espouse the New Zealand Māori values of Manaakitanga – about how communities care about each other’s wellbeing, nurture relationships, and engage with one another. But let me say this: In my over 30 years as a doctor, no patient I have attended to who was a victim of a violent unprovoked attack felt any sense of the community’s caring spirit.

At the Hubert Humphrey Building dedication, Nov. 1, 1977, in Washington, D.C., former vice president Humphrey said: “The moral test of government is how that government treats those who are in the dawn of life, the children; those who are in the twilight of life, the elderly; those who are in the shadows of life, the sick, the needy and the handicapped.” Should our Manaakitanga not extend to the whenua that need help and are vulnerable? Should someone with a mental disability not be able to walk to his neighbourhood restaurant wearing a red shirt? We need to demand that basic right of each other.

And, it should not only be the government, although they can help with fiscal or judicial deterrents for anyone to be even associated with a gang or committing a criminal offence. After all, we are a democracy. It should be us. As a society we have to say that violence towards a fellow New Zealander (or anyone in the country for that matter) is not acceptable. The solution is in “moral responsibility” and regular public discussions and education about what is unacceptable behaviour from an early age, and families and friends shunning violence or criminality even within their groups.

Last year, I was invited to speak at the Philosophy Colloquium at USF Humanities Institute in America by the team that runs the MIT Perspectives on Science Journal. Finding myself among a group of philosophy academics, there was a side discussion on the differences between collective responsibility and moral responsibility—something that perhaps can only happen in such gatherings.

One day a week I used to teach creative writing to low-decile school children, and we ran an annual short story competition, with the winning school receiving a library of books. These days my visits are less often, although my charitable foundation still runs literary and nutrition programmes in schools. When I saw stories written by these children it was clear that violence and abuse played a major part within families—something feared, but sadly also accepted. It always troubled me greatly that childhood in New Zealand was not a time for joyful dreams but bullies and stress. No wonder we have one of the highest youth suicide rates in the world.

Our youngsters revere our rugby teams as gods. In recent years, the All Blacks, our national rugby team of demi-gods have recently featured two players, Shannon Frizzell and Sevu Reece that had severely assaulted women, but in the one-eyed pursuit of winning, the country turned a blind eye and offered the players diversions. I’m not singling them out for any reason other than those stories made the news and didn’t stop them making national teams. Maybe we have to rethink our win-at-all-cost attitude. Maybe we must not tolerate bad behaviour from anyone, even our heroes. Because ultimately the price society pays for conflict and unrest is far greater. Our geographical distance from the rest of the world may mean we are at peace, but devoid of calm we will find that the self-adoration of our photographic beauty is no longer attractive to people we need to bring in to work in our health system, or study at our universities. Perhaps we must start with a national prescription for moral responsibility.

THE END

Written By

Dr Sharad Paul

Dr Sharad Paul is an award winning, world renowned recognised skin-cancer expert and thought-leader.