The gastronomic science of the gut is always interesting. Full of science—and sometimes—pseudoscience. Like I was told—when I was in Hong Kong to deliver a lecture a few years ago—that beef and chestnut, two foods considered “warm” in traditional Chinese medicine, could be harmful in summer due to hot body temperatures. I was told that the interactions between these foods would be akin to adding fuel to my body’s fire. I did try looking into this at a molecular level but drew a blank, pointing to the limitations of that narrative. Mangoes were also considered “hot fruits” in Hong Kong i.e., increasing body heat.

I travelled directly from Hong Kong to New Delhi enroute to the Jaipur Literature Festival in India. It is the world’s largest writers and book festival with over 500 thousand attendees! I met someone speaking on Ayurveda and was told mangoes were a summer fruit in India because they were cooling in nature! Go figure.

As an organ, our gut is our grandmother, and eating advice comes from our ancestral origins. These days exciting individual choices, unhealthy corporate forces and globalisation converge within the crucible that also houses our microbiome. Visually and microscopically concealed from the outside, our microbes are housed within havens, yet the human host’s lifestyle, genetic pasts, and modern medicines prove to be constant burdens.

How does one know what happens when foods end up in our gut? Can low calorie mix with high calorie? Do low fat foods have a gastronomic virtuousness over the proximity of highly processed ones? Isn’t the primary job of the stomach just to be an intestinal Insinkerator without any boundary between natural and manufactured foods?

We do know that there are some interactions between medicines and foods. This may be because of decreased absorption or interaction between chemicals in the pharmaceutical formulations and foods. Some examples:

• Grapefruit can potentiate blood pressure medications (especially calcium channel blockers such as felodipine, amlodipine etc) and increase blood pressure to dangerous levels, and also affect blood levels of cholesterol-lowering statins.

• Oatmeal affects the absorption of Digoxin, thereby reducing its effect.

• Leafy vegetables high in vitamin K such as broccoli, Brussels sprouts, spinach, and kale reduce the blood thinning effect of warfarin, and increase the risk of blood clots.

• Calcium-rich foods such as milk affect absorption of antibiotics such as tetracyclines and these drugs must not be taken within two hours of consuming dairy foods.

• Liquorice combines with the same receptors as spironolactone (medication used for blood pressure and heart failure, as well as increased hair growth) and can inactivate its benefit.

In my bestselling book, The Genetics of Health (Simon and Schuster, NYC)—now translated into German and Italian—I have a chapter on “eating for your gene type”. This is from the opening section of that chapter (page 180):

“The old adage about the way to a man’s heart being through the stomach makes food a currency of love—and for humans, a recent religion. The Italians practice it with great gusto, and the French excel in culinary catechism. But certain foods do make us happy, and others may cause illness in certain people due to genetic variations in our gut metabolisms—especially when diets are not balanced. When it comes to food etiquette, genes work on the concept of good and bad, rather than polite and rude.”

While researching for this book, I became interested in food-food interactions. In this article, I am going to specifically discuss berries and bananas.

Berries are superfoods, but the very potency that makes them beneficial means that they can interact with other foods. I was also interested in studying berries for another reason: my work and research in skin cancer, UV-related skin damage and sunscreens. Berries are high in flavonols and flavonoids which have antioxidant effects and are essential for protecting plants from UV radiation. Therefore, in this blog I am going to give you a few berry-useful tips, jumping between nutrition, composition and storage.

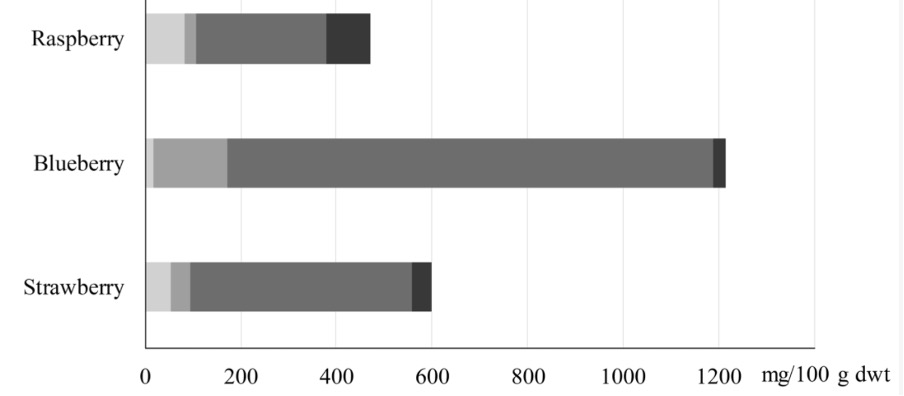

The graph (from Liu, Jiyun, Mohammed E. Hefni, and Cornelia M. Witthöft. 2020. “Characterization of Flavonoid Compounds in Common Swedish Berry Species” Foods 9, no. 3: 358) below shows the flavonol content of popular berries, with anthocyanins being the main flavonoids present in them.

Blueberries have almost twice the flavonoids as the other berries. However, we know they also contain the most sugar estimated at around 15g per cup of blueberries. Blackberries are similar to blueberries in antioxidant content. However, blackberries are less farmed and more likely to be closer to their ancestral forms. Raspberries have the least sugar, approximately 5g per cup. I have become increasingly appreciative of the cellular benefits of the above trio, with scientific studies showing a repertory ranging from benefits to cardiovascular health to reducing dementia.

The problem with strawberries is—perhaps underscored by its ascension to the pantheon of an English summer, they are the most tenaciously commercialised—it is very difficult to find them free of sprays and pesticides. In fact, the Environmental Working Group (EWG) lists strawberries at the top of the foods at risk of having pesticide residues. One of the problems is, being devoid of skin, washing strawberries doesn’t help because chemicals used in the soil grow into the berry itself, because it has no protective skin unlike other berries.

Maybe no other fruit is used as a literary device for secondary meanings as much as a banana. Whichever country you go to proverbs or colloquialisms abound about bananas. Downunder calling someone or oneself a “banana” means “silly”. Banana peels are more than slapstick comedy; they are metaphors for embarrassing failures or falls. Bananas are rich in potassium and serotonin, and when green they are full of resistant starch. When bananas are bruised or sliced and exposed to outside air, they turn brown. This is because of enzymatic browning due to oxidation that is mediated by an enzyme, polyphenol oxidase (PPO). But we know that PPO degrades the flavonols in berries. A study was conducted—by the Royal Society of Chemistry, no less—to see if this food interaction between bananas and berries was significant.

Participants were given a banana smoothie which has naturally high PPO activity, and a berry smoothie made with mixed berries, which has low PPO. The control group took a flavonol capsule. The study showed that adding a single banana to a bowl of berries meant a 84% reduction in flavanol levels. In other words, bananas when added to berries almost completely nullify the benefits of berries! It appears that cafes and cereal makers have unwittingly done us in for decades.

Nutritional benefits are a complex cellular artefact, and our human aim of good health has to comply with the reality of the laws of chemistry. Science doesn’t have much is the way of culinary critique other than a loud nutritional message: DO NOT MIX YOUR BANANAS AND BERRIES.

THE END

IMPORTANT: This blog is about science-communication, education, interesting new science, and medical research to do with (mostly) health and skin. It is not individual one-on-one medical advice. Please do not stop any medications without consulting your own doctor.

Written By

Dr Sharad Paul

Dr Sharad Paul is an award winning, world renowned recognised skin-cancer expert and thought-leader.