COFFEE: WHAT’S SKIN CANCER GOT TO DO WITH OUR FAVOURITE DRINK?

Your coffee habit may determine your skin cancer risk.

I have often been quoted as saying, “One cannot have bad skin and good health.” Skin merely reflects what lies beneath. What we eat and drink impacts how our skin looks and feels, but what about skin cancer? Does drinking coffee make any difference?

“I have measured out my life with coffee spoons” wrote T.S. Eliot in his famous The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock poem that was first published in Poetry magazine in 1915. He was alluding to his loneliness and mundane life, but coffee as a beverage has been known since the 15th century when the writings of Ahmed al-Ghaffar of Yemen in the Arabian Peninsula revealed that coffee was roasted, brewed, and consumed in the Arabian Peninsula, in a not dissimilar fashion to what happens today.

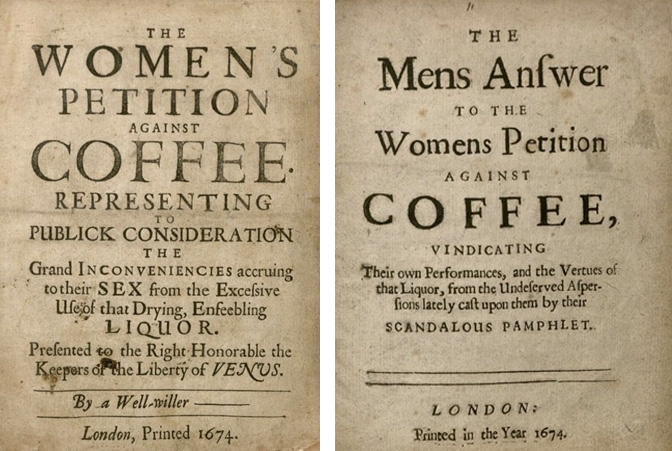

By the 16th century, it was clear that coffee had a special potency with many medicinal properties. But acceptance into a guilt-ridden English Christian society proved more difficult. Caffeine, the stimulant that influences mood as well as energy levels, ended up hosting a battle of the sexes, as we can see from the historical petitions below.

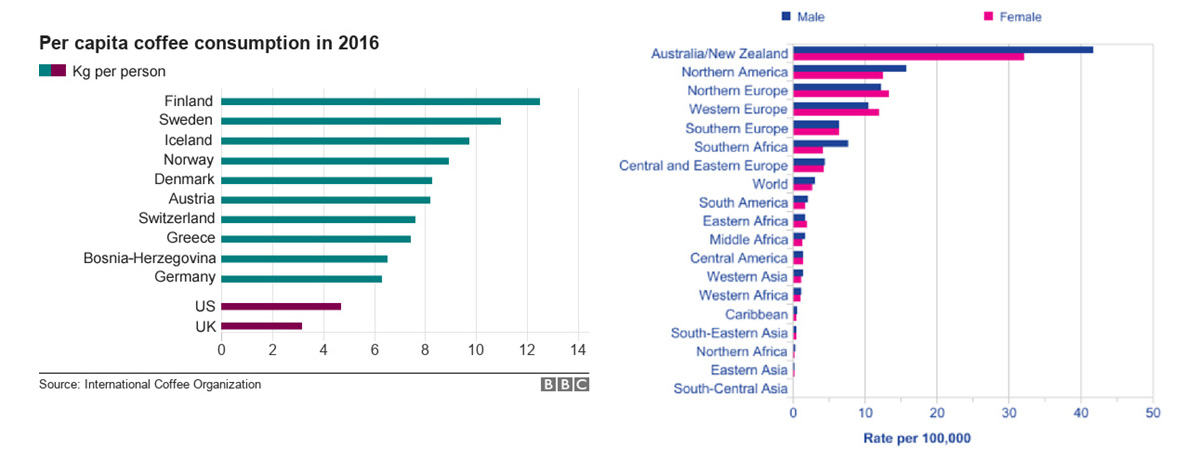

Nowadays, coffee is everywhere. As an unassuming coffee bean began to be spread around the world by traders and colonists, few would have envisioned the influence it would have. Down under in New Zealand and Australia, we have become coffee snobs. I ran a bookstore café, Baci Lounge, that won Auckland’s Best Café award in 2008. That makes me understand the grammar of coffee, and the covetousness of gentrified drinkers with global ambitions. Why, our invention, the flat white is now available in London and New York! Truth be told, Australasia is not the biggest consumer of this beverage. The heaviest coffee consumption is actually in the Scandinavian countries, according to the coffee industry. What the Antipodes is famous for, instead, is skin cancer.

.

Left: Chart courtesy of International Coffee Organization

Right: Chart courtesy of Akbarian F, Aarabi M, Shafiee MA. Melanoma Diagnostic Approach. Journal of Current Clinical Care Jan/Feb 2013

A few years ago, a study was conducted in Geraldton, Western Australia to investigate the association between caffeine intake and incidence of basal cell (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). This town on Australia’s Coral Coast, typical of subtropical Australian cities, has a high incidence of skin cancers. Would drinking coffee make any difference? That was what researchers wanted to find out.

1325 randomly selected adults were given questionnaires and asked to record their coffee consumption in 1992, 1994 and 1996. Following this for a ten-year period, all non-melanoma skin cancers i.e., BCC and SCC, were confirmed by pathology reports. Statistical analyses were performed on all skin cancers that occurred between 1997 and 2007 and the study group.

The results were interesting. For the average coffee drinker, drinking one to two cups of coffee a day—caffeinated or decaffeinated—had no influence on the number of skin cancers. But among those on the highest tertile—those in the third group that drank more than four cups of coffee a day—showed a 25% reduction is basal cell skin cancers (BCC) but not squamous cell skin cancers (SCC). For the latter, drinking coffee made no difference. In 2014, these researchers reported in the European Journal of Nutrition that among people with prior skin cancers, a relatively high caffeine intake may help prevent subsequent BCC development.

As a skin cancer doctor, educator, and academic, this had me interested. In clinical practice we find that BCC, like melanoma has a strong genetic predisposition as well as an association with sunburns, and intermittent overexposure to UV radiation. SCC, in contrast is more associated with prolonged sun exposure such as in farmers or sailors, and overrepresented in patients on immunosuppressant medications. Therefore, if coffee consumption affected BCC and not SCC, one would expect it to have a similar effect on melanoma. Indeed, that is exactly what another research group studied, and published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The coffee habits of almost 450,000 people were studied on non-Hispanic Caucasian subjects using a self-administered food-frequency questionnaire over 1995 and 1996. This large sample was then followed up for the subsequent 10 years. Similar to what was found with BCC, the highest coffee intake was inversely associated with a risk of malignant melanoma, with a 20% lower risk of melanoma for those who consumed four cups per day or more. Interestingly there was no difference in the less invasive melanoma in-situ group, but copious coffee drinking did reduce the risk of invasive melanoma.

However, the effect was statistically significant for caffeinated but not decaffeinated coffee, and only for protection against malignant melanoma but not melanoma in-situ, which may have a different aetiology. As it is often discussed at research conferences I attend, melanoma in-situ and invasive melanoma have a different biology. The former develops slowly as a changing freckle, and this is what doctors more commonly pick up when we see patients, and the patient is unaware of anything untoward. Invasive melanomas are usually rapidly growing and nodular, and in most cases the die is cast by the time the patient notices it i.e., the stage at diagnosis determines the outcome. Because melanoma in-situ is slow developing, for very old people or those not fit for surgery, even topical creams have been trialled.

Interestingly, the effect in all these studies was seen for coffee and not specifically caffeine. In other words, caffeine played a part, but something else in coffee was beneficial, and we now know it is to do with polyphenols that are present. Coffee may have its origins on the Ethiopian Plateau, but when the bean was let loose on our human bodies, it was obvious that it manipulated many of our metabolic systems and ended up an addictive sublimity. In addition to the obvious caffeine, other polyphenols in coffee, chlorogenic acid (CGA), diterpenes and trigonelline. In fact, studies have shown that coffee is one of the most polyphenol-rich beverages, containing 214 mg of total polyphenols per 100 ml. In our Western diets, among coffee drinkers, coffee is almost the biggest source phenolic acids and hydroxycinnamic acids, especially CGA[1].

Interestingly, another European group recently studied coffee and tea drinking and melanoma risk and reported that: “The reduction in melanoma risk among men was 10% for a linear increase in the consumption of caffeinated coffee by 100 mL/day, and 70% for those in the top country-specific quartile of consumption. We found no association between the consumption of caffeinated coffee and melanoma risk among women”. In this European study, unlike the evidence from the American researchers, the benefit was confined to men. Gender diversity ended up being damned by science.

But before you rush off and start drinking a lot of coffee, there are things to consider as with any medication: risks and side effects. Some studies have reported a link between high coffee consumption and increased risk of high blood pressure and heart disease, while other studies have shown no effect or even a protective effect with moderate intake. Why was this difference? We now know that this difference is in your genetic make-up.

In fact, two important studies[2] [3] have now shown that the effect of coffee on cardiovascular disease depends on a variation in a gene called CYP1A2. I remember being interviewed about this in London during an author event for my book, The Genetics of Health (Simon and Schuster) that discussed our genes, lifestyles and wellbeing. Some people metabolise coffee slowly. Variations in the CYP1A2 gene affect the rate at which caffeine is broken down, which in turn determines the impact of caffeine on heart health. Individuals who possess the GA or AA variant of CYP1A2 break down caffeine more slowly and are at greater risk of high blood pressure and heart attack when they consume more coffee. Those who have the GG variant indeed have a lower risk of heart disease with coffee consumption than those who consume no coffee at all. In case you want to find out your own coffee gene type, you can order a gene test specifically for your skin health here.

THE END.

1. Anna Tresserra-Rimbau, Alexander Medina-Remón et al. Coffee Polyphenols and High Cardiovascular Risk Parameters, Chapter 42 Editor(s): Victor R. Preedy, Coffee in Health and Disease Prevention 2015; Academic Press. Pages 387-394

2. Cornelis et al. Coffee, CYP1A2 genotype, and risk of myocardial infarction. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006; 295:1135-41

3.Palatini P et al. CYP1A2 genotype modifies the association between coffee intake and the risk of hypertension. Journal of Hypertension. 2009; 27:1594-1601.

Written By

Dr Sharad Paul

Dr Sharad Paul is an award winning, world renowned recognised skin-cancer expert and thought-leader.